Developing Strategy: Qualitative vs. Quantitative

The strategy development tools that I talk about at ClearPurpose tend to be qualitative in nature rather than quantitative. In other words, these tools deal with qualities that are difficult to measure using precise numbers. That makes many business decision makers uncomfortable.

Milton Friedman famously wrote an article titled, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits”¹ for the September 13, 1970 issue of the New York Times Magazine. His words memorialized what many businessmen (and economists) had been thinking — that being in business is all about making money and nothing else. In fact, in the U.S. today, we have such a litigious society that corporate executives and board members have the Shareholder Wealth Maximization principle pounded into their heads.

So, for many business leaders, any “strategic” decision is still all about the numbers — specifically the contribution to profit. Don’t get me wrong. I am fully on-board with the need to ensure that strategic decisions make financial sense. I also deeply understand that the growing availability of structured and unstructured data, combined with analytical tools, largely drawn from the fields of statistics and finance, can significantly enhance strategic decision making.

The reality is that, while the tools I talk about most are qualitative in nature, there’s serious financial analysis happening behind the scenes in most strategic development efforts in which I’m involved. This is good and healthy. Organizations typically have financial objectives to which they are held accountable. Differences in the financial contributions of different strategic options can also be incredibly helpful in making strategic decisions. We just need to guard against making decisions purely on a financial basis and not accounting for all aspects of strategic alignment that I focus on at ClearPurpose.

As an example of financial analysis used in making strategic decisions, consider the use of Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) at Sprint. As a mature business with tens of millions of customers, we had plenty of data to be able to calculate CLV for just about any subpopulation you might want to examine. We could consider CLV by geography, by sales channel, by what type of phone they had, by what price plan they were on, or by any of a variety of behaviors (e.g., how often they used push-to-talk).

For starters, this gave us an idea of which customers were most valuable, so as we evaluated different options in developing a strategy, by forecasting the impact on the number of different types of customers, we could quickly get a sense for which option created or destroyed the most value. But we could also forecast how different options might change the underlying factors used in calculating CLV, and then we could model the value created or destroyed based on these changes.

Customer Lifetime Value can be a very powerful tool for strategic analysis. Many organizations calculate CLV based solely on the lifetime revenue, but it is more helpful to consider the operating profit that each customer contributes. Using this definition, a simple formula for CLV would be:

CLV = Total Lifetime Revenue from the Customer —

Total Lifetime Cost to Serve the Customer —

Cost to Acquire the Customer

For a customer with recurring purchases (or, for example, a monthly subscription), then it becomes:

CLV = (# of Months as a Customers) x

(Revenue per Month — Cost to Serve per Month) —

Cost to Acquire

Or stated slightly differently,

CLV = (Revenue per Month — Cost to Serve per Month) / (Monthly Customer Churn) — Cost to Acquire

So, for comparing different strategic options, if one is expected to increase revenue per month, another is expected to reduce churn, and another is expected to reduce customer acquisition costs, then each of those changes can be modeled to see the impact on customer lifetime value (and expected long term contribution to the business).

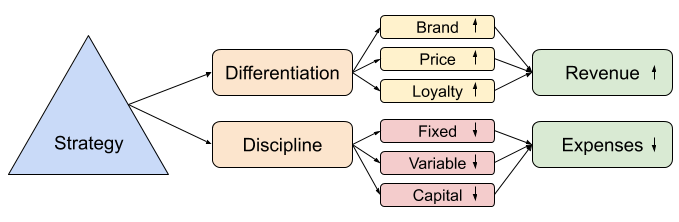

However, I would argue that there really is no conflict between the qualitative aspects of strategy and the desire to maximize business financial success. Businesses exist at the pleasure of their customers. A sound strategy will be based upon the desires of the market and the capabilities of the organization. Supposedly financially-driven decisions that either fail to serve real market needs or that cannot be effectively performed by the organization will not deliver the expected financial results.

I might even go so far as to argue that the “discount rate” used in valuing different options should be determined based on strategic alignment. The more aligned an option is with the strategy, the greater the likelihood of successful execution, so the lower risk leads to a lower discount rate (and the higher the calculated present value).

Bottom line, when developing strategy, it’s never an either/or decision between qualitative and quantitative tools, but rather a question of how to use both in a manner that makes sense for the decision being made.

Sources:

¹Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.umich.edu/~thecore/doc/Friedman.pdf on 8 July 2020.